LLM Evals: Everything You Need to Know

This document curates the most common questions Shreya and I received while teaching 700+ engineers & PMs AI Evals. Warning: These are sharp opinions about what works in most cases. They are not universal truths. Use your judgment.

👉 Want to learn more about AI Evals? Check out our AI Evals course. It’s a live cohort with hands on exercises and office hours. Here is a 25% discount code for readers. 👈

Listen to the audio version of this FAQ

If you prefer to listen to the audio version (narrated by AI), you can play it here.

Getting Started & Fundamentals

Q: What are LLM Evals?

If you are completely new to product-specific LLM evals (not foundation model benchmarks), see these posts: part 1, part 2 and part 3. Otherwise, keep reading.

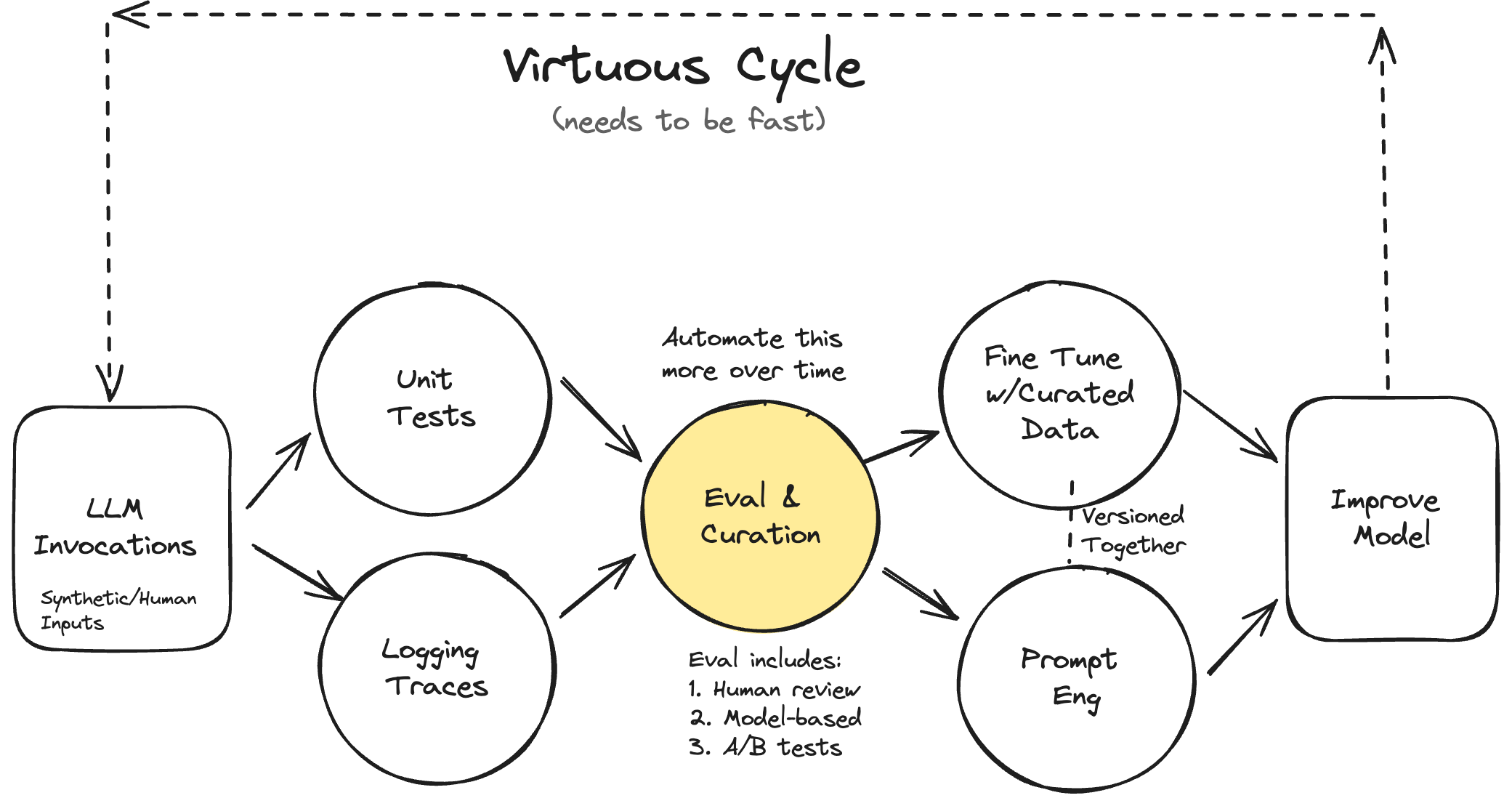

Your AI Product Needs Eval (Evaluation Systems)

Contents:

- Motivation

- Iterating Quickly == Success

- Case Study: Lucy, A Real Estate AI Assistant

- The Types Of Evaluation

- Level 1: Unit Tests

- Level 2: Human & Model Eval

- Level 3: A/B Testing

- Evaluating RAG

- Eval Systems Unlock Superpowers For Free

- Fine-Tuning

- Data Synthesis & Curation

- Debugging

Creating a LLM-as-a-Judge That Drives Business Results

Contents:

- The Problem: AI Teams Are Drowning in Data

- Step 1: Find The Principal Domain Expert

- Step 2: Create a Dataset

- Step 3: Direct The Domain Expert to Make Pass/Fail Judgments with Critiques

- Step 4: Fix Errors

- Step 5: Build Your LLM as A Judge, Iteratively

- Step 6: Perform Error Analysis

- Step 7: Create More Specialized LLM Judges (if needed)

- Recap of Critique Shadowing

- Resources

A Field Guide to Rapidly Improving AI Products

Contents:

- How error analysis consistently reveals the highest-ROI improvements

- Why a simple data viewer is your most important AI investment

- How to empower domain experts (not just engineers) to improve your AI

- Why synthetic data is more effective than you think

- How to maintain trust in your evaluation system

- Why your AI roadmap should count experiments, not features

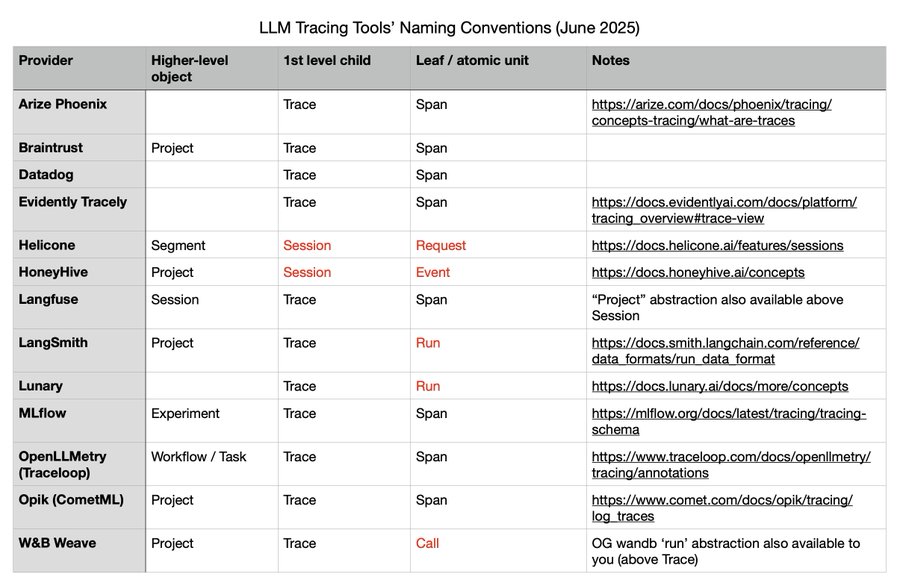

Q: What is a trace?

A trace is the complete record of all actions, messages, tool calls, and data retrievals from a single initial user query through to the final response. It includes every step across all agents, tools, and system components in a session: multiple user messages, assistant responses, retrieved documents, and intermediate tool interactions.

Note on terminology: Different observability vendors use varying definitions of traces and spans. Alex Strick van Linschoten’s analysis highlights these differences (screenshot below):

Q: What’s a minimum viable evaluation setup?

Start with error analysis, not infrastructure. Spend 30 minutes manually reviewing 20-50 LLM outputs whenever you make significant changes. Use one domain expert who understands your users as your quality decision maker (a “benevolent dictator”).

If possible, use notebooks to help you review traces and analyze data. In our opinion, this is the single most effective tool for evals because you can write arbitrary code, visualize data, and iterate quickly. You can even build your own custom annotation interface right inside notebooks, as shown in this video.

Q: How much of my development budget should I allocate to evals?

It’s important to recognize that evaluation is part of the development process rather than a distinct line item, similar to how debugging is part of software development.

You should always be doing error analysis. When you discover issues through error analysis, many will be straightforward bugs you’ll fix immediately. These fixes don’t require separate evaluation infrastructure as they’re just part of development.

The decision to build automated evaluators comes down to cost-benefit analysis. If you can catch an error with a simple assertion or regex check, the cost is minimal and probably worth it. But if you need to align an LLM-as-judge evaluator, consider whether the failure mode warrants that investment.

In the projects we’ve worked on, we’ve spent 60-80% of our development time on error analysis and evaluation. Expect most of your effort to go toward understanding failures (i.e. looking at data) rather than building automated checks.

Be wary of optimizing for high eval pass rates. If you’re passing 100% of your evals, you’re likely not challenging your system enough. A 70% pass rate might indicate a more meaningful evaluation that’s actually stress-testing your application. Focus on evals that help you catch real issues, not ones that make your metrics look good.

Q: Will today’s evaluation methods still be relevant in 5-10 years given how fast AI is changing?

Yes. Even with perfect models, you still need to verify they’re solving the right problem. The need for systematic error analysis, domain-specific testing, and monitoring will still be important.

Today’s prompt engineering tricks might become obsolete, but you’ll still need to understand failure modes. Additionally, a LLM cannot read your mind, and research shows that people need to observe the LLM’s behavior in order to properly externalize their requirements.

For deeper perspective on this debate, see these two viewpoints: “The model is the product” versus “The model is NOT the product”.

“The model is the product”:

“The model is NOT the product”:

Q: How do I make the case for investing in evaluations to my team?

Don’t try to sell your team on “evals”. Instead, show them what you find when you look at the data.

Start by doing the error analysis yourself. Look at 50 to 100 real user conversations and find the most common ways the product is failing. Use these findings to tell a story with data.

Present your team with:

- A list of the top failure modes you discovered.

- Metrics showing how often high-impact errors are happening.

- Surprising ways that users are interacting with the product.

- Reports on the bugs you found and fixed, framed as “prevented production issues”.

This approach builds trust. Don’t just show dashboards and metrics; tell the story of what you’re finding in the data. By narrating your findings, you teach the team what you’re learning, providing immediate value. When you fix an issue, show how the error rate for that specific problem went down. Soon, your team will see the progress and ask how you’re doing it. Let results instead of methods lead the conversation.

This is similar to classic machine learning projects, where outcomes are speculative and progress is bounded by iterating on experiments. In this situation, it’s important that you share the learnings from each experiment to show progress and encourage investment.

Error Analysis & Data Collection

Q: Why is "error analysis" so important in LLM evals, and how is it performed?

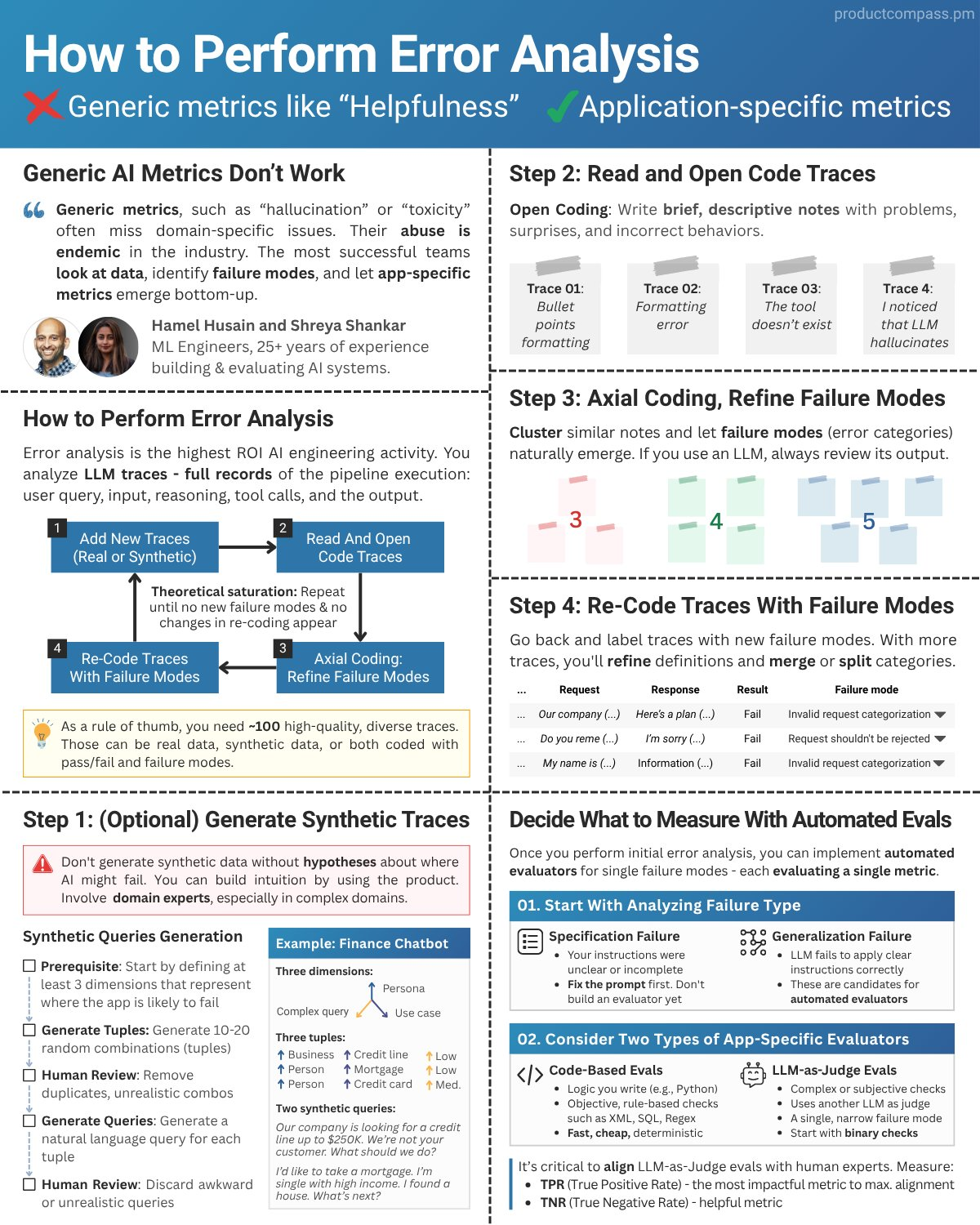

Error analysis is the most important activity in evals. Error analysis helps you decide what evals to write in the first place. It allows you to identify failure modes unique to your application and data. The process involves:

1. Creating a Dataset

Gathering representative traces of user interactions with the LLM. If you do not have any data, you can generate synthetic data to get started.

2. Open Coding

Human annotator(s) (ideally a benevolent dictator) review and write open-ended notes about traces, noting any issues. This process is akin to “journaling” and is adapted from qualitative research methodologies. When beginning, it is recommended to focus on noting the first failure observed in a trace, as upstream errors can cause downstream issues, though you can also tag all independent failures if feasible. A domain expert should be performing this step.

3. Axial Coding

Categorize the open-ended notes into a “failure taxonomy.”. In other words, group similar failures into distinct categories. This is the most important step. At the end, count the number of failures in each category. You can use a LLM to help with this step.

4. Iterative Refinement

Keep iterating on more traces until you reach theoretical saturation, meaning new traces do not seem to reveal new failure modes or information to you. As a rule of thumb, you should aim to review at least 100 traces.

You should frequently revisit this process. There are advanced ways to sample data more efficiently, like clustering, sorting by user feedback, and sorting by high probability failure patterns. Over time, you’ll develop a “nose” for where to look for failures in your data.

Do not skip error analysis. It ensures that the evaluation metrics you develop are supported by real application behaviors instead of counter-productive generic metrics (which most platforms nudge you to use). For examples of how error analysis can be helpful, see this video, or this blog post.

Here is a visualization of the error analysis process by one of our students, Pawel Huryn - including how it fits into the overall evaluation process:

Q: How do I surface problematic traces for review beyond user feedback?

While user feedback is a good way to narrow in on problematic traces, other methods are also useful. Here are three complementary approaches:

Start with random sampling

The simplest approach is reviewing a random sample of traces. If you find few issues, escalate to stress testing: create queries that deliberately test your prompt constraints to see if the AI follows your rules.

Use evals for initial screening

Use existing evals to find problematic traces and potential issues. Once you’ve identified these, you can proceed with the typical evaluation process starting with error analysis.

Leverage efficient sampling strategies

For more sophisticated trace discovery, use outlier detection, metric-based sorting, and stratified sampling to find interesting traces. Generic metrics can serve as exploration signals to identify traces worth reviewing, even if they don’t directly measure quality.

Q: How often should I re-run error analysis on my production system?

Re-run error analysis when making significant changes: new features, prompt updates, model switches, or major bug fixes. A useful heuristic is to set a goal for reviewing at least 100+ fresh traces each review cycle. Typical review cycles we’ve seen range from 2-4 weeks. See this FAQ on how to sample traces effectively.

Between major analyses, review 10-20 traces weekly, focusing on outliers: unusually long conversations, sessions with multiple retries, or traces flagged by automated monitoring. Adjust frequency based on system stability and usage growth. New systems need weekly analysis until failure patterns stabilize. Mature systems might need only monthly analysis unless usage patterns change. Always analyze after incidents, user complaint spikes, or metric drift. Scaling usage introduces new edge cases.

Q: What is the best approach for generating synthetic data?

A common mistake is prompting an LLM to "give me test queries" without structure, resulting in generic, repetitive outputs. A structured approach using dimensions produces far better synthetic data for testing LLM applications.

Start by defining dimensions: categories that describe different aspects of user queries. Each dimension captures one type of variation in user behavior. For example:

- For a recipe app, dimensions might include Dietary Restriction (vegan, gluten-free, none), Cuisine Type (Italian, Asian, comfort food), and Query Complexity (simple request, multi-step, edge case).

- For a customer support bot, dimensions could be Issue Type (billing, technical, general), Customer Mood (frustrated, neutral, happy), and Prior Context (new issue, follow-up, resolved).

Start with failure hypotheses. If you lack intuition about failure modes, use your application extensively or recruit friends to use it. Then choose dimensions targeting those likely failures.

Create tuples manually first: Write 20 tuples by hand—specific combinations selecting one value from each dimension. Example: (Vegan, Italian, Multi-step). This manual work helps you understand your problem space.

Scale with two-step generation:

- Generate structured tuples: Have the LLM create more combinations like (Gluten-free, Asian, Simple)

- Convert tuples to queries: In a separate prompt, transform each tuple into natural language

This separation avoids repetitive phrasing. The (Vegan, Italian, Multi-step) tuple becomes: "I need a dairy-free lasagna recipe that I can prep the day before."

Generation approaches

You can generate tuples two ways:

Cross product then filter: Generate all dimension combinations, then filter with an LLM. Guarantees coverage including edge cases. Use when most combinations are valid.

Direct LLM generation: Ask the LLM to generate tuples directly. More realistic but tends toward generic outputs and misses rare scenarios. Use when many dimension combinations are invalid.

Fix obvious problems first: Don’t generate synthetic data for issues you can fix immediately. If your prompt doesn’t mention dietary restrictions, fix the prompt rather than generating specialized test queries.

After iterating on your tuples and prompts, run these synthetic queries through your actual system to capture full traces. Sample 100 traces for error analysis. This number provides enough traces to manually review and identify failure patterns without being overwhelming.

Q: Are there scenarios where synthetic data may not be reliable?

Yes: synthetic data can mislead or mask issues. For guidance on generating synthetic data when appropriate, see What is the best approach for generating synthetic data?

Common scenarios where synthetic data fails:

Complex domain-specific content: LLMs often miss the structure, nuance, or quirks of specialized documents (e.g., legal filings, medical records, technical forms). Without real examples, critical edge cases are missed.

Low-resource languages or dialects: For low-resource languages or dialects, LLM-generated samples are often unrealistic. Evaluations based on them won’t reflect actual performance.

When validation is impossible: If you can’t verify synthetic sample realism (due to domain complexity or lack of ground truth), real data is important for accurate evaluation.

High-stakes domains: In high-stakes domains (medicine, law, emergency response), synthetic data often lacks subtlety and edge cases. Errors here have serious consequences, and manual validation is difficult.

Underrepresented user groups: For underrepresented user groups, LLMs may misrepresent context, values, or challenges. Synthetic data can reinforce biases in the training data of the LLM.

Q: How do I approach evaluation when my system handles diverse user queries?

Complex applications often support vastly different query patterns—from “What’s the return policy?” to “Compare pricing trends across regions for products matching these criteria.” Each query type exercises different system capabilities, leading to confusion on how to design eval criteria.

Error Analysis is all you need. Your evaluation strategy should emerge from observed failure patterns (e.g. error analysis), not predetermined query classifications. Rather than creating a massive evaluation matrix covering every query type you can imagine, let your system’s actual behavior guide where you invest evaluation effort.

During error analysis, you’ll likely discover that certain query categories share failure patterns. For instance, all queries requiring temporal reasoning might struggle regardless of whether they’re simple lookups or complex aggregations. Similarly, queries that need to combine information from multiple sources might fail in consistent ways. These patterns discovered through error analysis should drive your evaluation priorities. It could be that query category is a fine way to group failures, but you don’t know that until you’ve analyzed your data.

To see an example of basic error analysis in action, see this video.

Q: How can I efficiently sample production traces for review?

It can be cumbersome to review traces randomly, especially when most traces don’t have an error. These sampling strategies help you find traces more likely to reveal problems:

- Outlier detection: Sort by any metric (response length, latency, tool calls) and review extremes.

- User feedback signals: Prioritize traces with negative feedback, support tickets, or escalations.

- Metric-based sorting: Generic metrics can serve as exploration signals to find interesting traces. Review both high and low scores and treat them as exploration clues. Based on what you learn, you can build custom evaluators for the failure modes you find.

- Stratified sampling: Group traces by key dimensions (user type, feature, query category) and sample from each group.

- Embedding clustering: Generate embeddings of queries and cluster them to reveal natural groupings. Sample proportionally from each cluster, but oversample small clusters for edge cases. There’s no right answer for clustering—it’s an exploration technique to surface patterns you might miss manually.

As you get more sophisticated with how you sample, you can incorporate these tactics into the design of your annotation tools.

👉 Want to learn more about AI Evals? Check out our AI Evals course. It’s a live cohort with hands on exercises and office hours. Here is a 25% discount code for readers. 👈

Evaluation Design & Methodology

Q: Why do you recommend binary (pass/fail) evaluations instead of 1-5 ratings (Likert scales)?

Engineers often believe that Likert scales (1-5 ratings) provide more information than binary evaluations, allowing them to track gradual improvements. However, this added complexity often creates more problems than it solves in practice.

Binary evaluations force clearer thinking and more consistent labeling. Likert scales introduce significant challenges: the difference between adjacent points (like 3 vs 4) is subjective and inconsistent across annotators, detecting statistical differences requires larger sample sizes, and annotators often default to middle values to avoid making hard decisions.

Having binary options forces people to make a decision rather than hiding uncertainty in middle values. Binary decisions are also faster to make during error analysis - you don’t waste time debating whether something is a 3 or 4.

For tracking gradual improvements, consider measuring specific sub-components with their own binary checks rather than using a scale. For example, instead of rating factual accuracy 1-5, you could track “4 out of 5 expected facts included” as separate binary checks. This preserves the ability to measure progress while maintaining clear, objective criteria.

Start with binary labels to understand what ‘bad’ looks like. Numeric labels are advanced and usually not necessary.

Q: Should I practice eval-driven development?

Generally no. Eval-driven development (writing evaluators before implementing features) sounds appealing but creates more problems than it solves. Unlike traditional software where failure modes are predictable, LLMs have infinite surface area for potential failures. You can’t anticipate what will break.

A better approach is to start with error analysis. Write evaluators for errors you discover, not errors you imagine. This avoids getting blocked on what to evaluate and prevents wasted effort on metrics that have no impact on actual system quality.

Exception: Eval-driven development may work for specific constraints where you know exactly what success looks like. If adding “never mention competitors,” writing that evaluator early may be acceptable.

Most importantly, always do a cost-benefit analysis before implementing an eval. Ask whether the failure mode justifies the investment. Error analysis reveals which failures actually matter for your users.

Q: Should I build automated evaluators for every failure mode I find?

Focus automated evaluators on failures that persist after fixing your prompts. Many teams discover their LLM doesn’t meet preferences they never actually specified - like wanting short responses, specific formatting, or step-by-step reasoning. Fix these obvious gaps first before building complex evaluation infrastructure.

Consider the cost hierarchy of different evaluator types. Simple assertions and reference-based checks (comparing against known correct answers) are cheap to build and maintain. LLM-as-Judge evaluators require 100+ labeled examples, ongoing weekly maintenance, and coordination between developers, PMs, and domain experts. This cost difference should shape your evaluation strategy.

Only build expensive evaluators for problems you’ll iterate on repeatedly. Since LLM-as-Judge comes with significant overhead, save it for persistent generalization failures - not issues you can fix trivially. Start with cheap code-based checks where possible: regex patterns, structural validation, or execution tests. Reserve complex evaluation for subjective qualities that can’t be captured by simple rules.

Q: Should I use "ready-to-use" evaluation metrics?

No. Generic evaluations waste time and create false confidence. (Unless you’re using them for exploration).

One instructor noted:

“All you get from using these prefab evals is you don’t know what they actually do and in the best case they waste your time and in the worst case they create an illusion of confidence that is unjustified.”1

Generic evaluation metrics are everywhere. Eval libraries contain scores like helpfulness, coherence, quality, etc. promising easy evaluation. These metrics measure abstract qualities that may not matter for your use case. Good scores on them don’t mean your system works.

Instead, conduct error analysis to understand failures. Define binary failure modes based on real problems. Create custom evaluators for those failures and validate them against human judgment. Essentially, the entire evals process.

Experienced practitioners may still use these metrics, just not how you’d expect. As Picasso said: “Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.” Once you understand why generic metrics fail as evaluations, you can repurpose them as exploration tools to find interesting traces (explained in the next FAQ).

Q: Are similarity metrics (BERTScore, ROUGE, etc.) useful for evaluating LLM outputs?

Generic metrics like BERTScore, ROUGE, cosine similarity, etc. are not useful for evaluating LLM outputs in most AI applications. Instead, we recommend using error analysis to identify metrics specific to your application’s behavior. We recommend designing binary pass/fail.) evals (using LLM-as-judge) or code-based assertions.

As an example, consider a real estate CRM assistant. Suggesting showings that aren’t available (can be tested with an assertion) or confusing client personas (can be tested with a LLM-as-judge) is problematic . Generic metrics like similarity or verbosity won’t catch this. A relevant quote from the course:

“The abuse of generic metrics is endemic. Many eval vendors promote off the shelf metrics, which ensnare engineers into superfluous tasks.”

Similarity metrics aren’t always useless. They have utility in domains like search and recommendation (and therefore can be useful for optimizing and debugging retrieval for RAG). For example, cosine similarity between embeddings can measure semantic closeness in retrieval systems, and average pairwise similarity can assess output diversity (where lower similarity indicates higher diversity).

Q: Can I use the same model for both the main task and evaluation?

For LLM-as-Judge selection, using the same model is usually fine because the judge is doing a different task than your main LLM pipeline. While research has shown that models can exhibit bias when evaluating their own outputs, what ultimately matters is how well your judge aligns with human judgments. The judges we recommend building do scoped binary classification tasks. We’ve found that iterative alignment with human labels is usually achievable on this constrained task.

Focus on achieving high True Positive Rate (TPR) and True Negative Rate (TNR) with your judge on a held out labeled test set. If you struggle to achieve good alignment with human scores, then consider trying a different model. However onboarding new model providers may involve non-trivial effort in some organizations, which is why we don’t advocate for using different models by default unless there’s a specific alignment issue.

When selecting judge models, start with the most capable models available to establish strong alignment with human judgments. You can optimize for cost later once you’ve established reliable evaluation criteria.

Q: How do we evaluate a model’s ability to express uncertainty or "know what it doesn’t know"?

Many applications require a model that can refuse to answer a question when it lacks sufficient information. To evaluate whether this refusal behavior is well-calibrated, you need to test if the model refuses at the appropriate times without refusing to answer questions it should be able to answer.

To do this effectively, you should construct an evaluation set that has the following components:

- Answerable Questions: Scenarios where a correct, verifiable answer is present in the model’s provided context or general knowledge.

- Unanswerable Questions: Scenarios designed to tempt the model to hallucinate. These include questions with false premises, queries about information explicitly missing from context, or topics far outside its knowledge base.

While the exact proportion isn’t critical, a balanced set with a roughly equal number of answerable and unanswerable questions is a good starting point. The diversity and difficulty of the questions are more important than the precise ratio.

The evaluation itself is a binary (Pass/Fail) check of the model’s judgment. A “Pass” requires the model to satisfy two conditions: it must answer the answerable questions while also refusing to answer the unanswerable ones. A failure is defined as providing a fabricated answer to an unanswerable question, which indicates poor calibration.

In the research literature, this capability is known as “Abstention Ability.” To improve this behavior, it is worth searching for this term on Arxiv to understand the latest techniques.

👉 Want to learn more about AI Evals? Check out our AI Evals course. It’s a live cohort with hands on exercises and office hours. Here is a 25% discount code for readers. 👈

Human Annotation & Process

Q: How many people should annotate my LLM outputs?

For most small to medium-sized companies, appointing a single domain expert as a “benevolent dictator” is the most effective approach. This person—whether it’s a psychologist for a mental health chatbot, a lawyer for legal document analysis, or a customer service director for support automation—becomes the definitive voice on quality standards.

A single expert eliminates annotation conflicts and prevents the paralysis that comes from “too many cooks in the kitchen”. The benevolent dictator can incorporate input and feedback from others, but they drive the process. If you feel like you need five subject matter experts to judge a single interaction, it’s a sign your product scope might be too broad.

However, larger organizations or those operating across multiple domains (like a multinational company with different cultural contexts) may need multiple annotators. When you do use multiple people, you’ll need to measure their agreement using metrics like Cohen’s Kappa, which accounts for agreement beyond chance. However, use your judgment. Even in larger companies, a single expert is often enough.

Start with a benevolent dictator whenever feasible. Only add complexity when your domain demands it.

Q: Should product managers and engineers collaborate on error analysis? How?

At the outset, collaborate to establish shared context. Engineers catch technical issues like retrieval issues and tool errors. PMs identify product failures like unmet user expectations, confusing responses, or missing features users expect.

As time goes on you should lean towards a benevolent dictator for error analysis: a domain expert or PM who understands user needs. Empower domain experts to evaluate actual outcomes rather than technical implementation. Ask “Has an appointment been made?” not “Did the tool call succeed?” The best way to empower the domain expert is to give them custom annotation tools that display system outcomes alongside traces. Show the confirmation, generated email, or database update that validates goal completion. Keep all context on one screen so non-technical reviewers focus on results.

Q: Should I outsource annotation & labeling to a third party?

Outsourcing error analysis is usually a big mistake (with some exceptions). The core of evaluation is building the product intuition that only comes from systematically analyzing your system’s failures. You should be extremely skeptical of this process being delegated.

The Dangers of Outsourcing

When you outsource annotation, you often break the feedback loop between observing a failure and understanding how to improve the product. Problems with outsourcing include:

- Superficial Labeling: Even well-defined metrics require nuanced judgment that external teams lack. A critical misstep in error analysis is excluding domain experts from the labeling process. Outsourcing this task to those without domain expertise, like general developers or IT staff, often leads to superficial or incorrect labeling.

- Loss of Unspoken Knowledge: A principal domain expert possesses tacit knowledge and user understanding that cannot be fully captured in a rubric. Involving these experts helps uncover their preferences and expectations, which they might not be able to fully articulate upfront.

- Annotation Conflicts and Misalignment: Without a shared context, external annotators can create more disagreement than they resolve. Achieving alignment is a challenge even for internal teams, which means you will spend even more time on this process.

The Recommended Approach: Build Internal Capability

Instead of outsourcing, focus on building an efficient internal evaluation process.

1. Appoint a “Benevolent Dictator”. For most teams, the most effective strategy is to appoint a single, internal domain expert as the final decision-maker on quality. This individual sets the standard, ensures consistency, and develops a sense of ownership.

2. Use a collaborative workflow for multiple annotators. If multiple annotators are necessary, follow a structured process to ensure alignment: * Draft an initial rubric with clear Pass/Fail definitions and examples. * Have each annotator label a shared set of traces independently to surface differences in interpretation. * Measure Inter-Annotator Agreement (IAA) using a chance-corrected metric like Cohen’s Kappa. * Facilitate alignment sessions to discuss disagreements and refine the rubric. * Iterate on this process until agreement is consistently high.

How to Handle Capacity Constraints

Building internal capacity does not mean you have to label every trace. Use these strategies to manage the workload:

- Smart Sampling: Review a small, representative sample of traces thoroughly. It is more effective to analyze 100 diverse traces to find patterns than to superficially label thousands.

- The “Think-Aloud” Protocol: To make the most of limited expert time, use this technique from usability testing. Ask an expert to verbalize their thought process while reviewing a handful of traces. This method can uncover deep insights in a single one-hour session.

- Build Lightweight Custom Tools: Build custom annotation tools to streamline the review process, increasing throughput.

Exceptions for External Help

While outsourcing the core error analysis process is not recommended, there are some scenarios where external help is appropriate:

- Purely Mechanical Tasks: For highly objective, unambiguous tasks like identifying a phone number or validating an email address, external annotators can be used after a rigorous internal process has defined the rubric.

- Tasks Without Product Context: Well-defined tasks that don’t require understanding your product’s specific requirements can be outsourced. Translation is a good example: it requires linguistic expertise but not deep product knowledge.

- Engaging Subject Matter Experts: Hiring external SMEs to act as your internal domain experts is not outsourcing; it is bringing the necessary expertise into your evaluation process. For example, AnkiHub hired 4th-year medical students to evaluate their RAG systems for medical content rather than outsourcing to generic annotators.

Q: What parts of evals can be automated with LLMs?

LLMs can speed up parts of your eval workflow, but they can’t replace human judgment where your expertise is essential. For example, if you let an LLM handle all of error analysis (i.e., reviewing and annotating traces), you might overlook failure cases that matter for your product. Suppose users keep mentioning “lag” in feedback, but the LLM lumps these under generic “performance issues” instead of creating a “latency” category. You’d miss a recurring complaint about slow response times and fail to prioritize a fix.

That said, LLMs are valuable tools for accelerating certain parts of the evaluation workflow when used with oversight.

Here are some areas where LLMs can help:

- First-pass axial coding: After you’ve open coded 30–50 traces yourself, use an LLM to organize your raw failure notes into proposed groupings. This helps you quickly spot patterns, but always review and refine the clusters yourself. Note: If you aren’t familiar with axial and open coding, see this faq.

- Mapping annotations to failure modes: Once you’ve defined failure categories, you can ask an LLM to suggest which categories apply to each new trace (e.g., “Given this annotation: [open_annotation] and these failure modes: [list_of_failure_modes], which apply?”).

- Suggesting prompt improvements: When you notice recurring problems, have the LLM propose concrete changes to your prompts. Review these suggestions before adopting any changes.

- Analyzing annotation data: Use LLMs or AI-powered notebooks to find patterns in your labels, such as “reports of lag increase 3x during peak usage hours” or “slow response times are mostly reported from users on mobile devices.”

However, you shouldn’t outsource these activities to an LLM:

- Initial open coding: Always read through the raw traces yourself at the start. This is how you discover new types of failures, understand user pain points, and build intuition about your data. Never skip this or delegate it.

- Validating failure taxonomies: LLM-generated groupings need your review. For example, an LLM might group both “app crashes after login” and “login takes too long” under a single “login issues” category, even though one is a stability problem and the other is a performance problem. Without your intervention, you’d miss that these issues require different fixes.

- Ground truth labeling: For any data used for testing/validating LLM-as-Judge evaluators, hand-validate each label. LLMs can make mistakes that lead to unreliable benchmarks.

- Root cause analysis: LLMs may point out obvious issues, but only human review will catch patterns like errors that occur in specific workflows or edge cases—such as bugs that happen only when users paste data from Excel.

In conclusion, start by examining data manually to understand what’s actually going wrong. Use LLMs to scale what you’ve learned, not to avoid looking at data.

Q: Should I stop writing prompts manually in favor of automated tools?

Automating prompt engineering can be tempting, but you should be skeptical of tools that promise to optimize prompts for you, especially in early stages of development. When you write a prompt, you are forced to clarify your assumptions and externalize your requirements. Good writing is good thinking 2. If you delegate this task to an automated tool too early, you risk never fully understanding your own requirements or the model’s failure modes.

This is because automated prompt optimization typically hill-climb a predefined evaluation metric. It can refine a prompt to perform better on known failures, but it cannot discover new ones. Discovering new errors requires error analysis. Furthermore, research shows that evaluation criteria tends to shift after reviewing a model’s outputs, a phenomenon known as “criteria drift” 3. This means that evaluation is an iterative, human-driven sensemaking process, not a static target that can be set once and handed off to an optimizer.

A pragmatic approach is to use LLMs to improve your prompt based on open coding (open-ended notes about traces). This way, you maintain a human in the loop who is looking at the data and externalizing their requirements. Once you have a high-quality set of evals, prompt optimization can be effective for that last mile of performance.

👉 Want to learn more about AI Evals? Check out our AI Evals course. It’s a live cohort with hands on exercises and office hours. Here is a 25% discount code for readers. 👈

Tools & Infrastructure

Q: Should I build a custom annotation tool or use something off-the-shelf?

Build a custom annotation tool. This is the single most impactful investment you can make for your AI evaluation workflow. With AI-assisted development tools like Cursor or Lovable, you can build a tailored interface in hours. I often find that teams with custom annotation tools iterate ~10x faster.

Custom tools excel because:

- They show all your context from multiple systems in one place

- They can render your data in a product specific way (images, widgets, markdown, buttons, etc.)

- They’re designed for your specific workflow (custom filters, sorting, progress bars, etc.)

Off-the-shelf tools may be justified when you need to coordinate dozens of distributed annotators with enterprise access controls. Even then, many teams find the configuration overhead and limitations aren’t worth it.

Isaac’s Anki flashcard annotation app shows the power of custom tools—handling 400+ results per query with keyboard navigation and domain-specific evaluation criteria that would be nearly impossible to configure in a generic tool.

Q: What makes a good custom interface for reviewing LLM outputs?

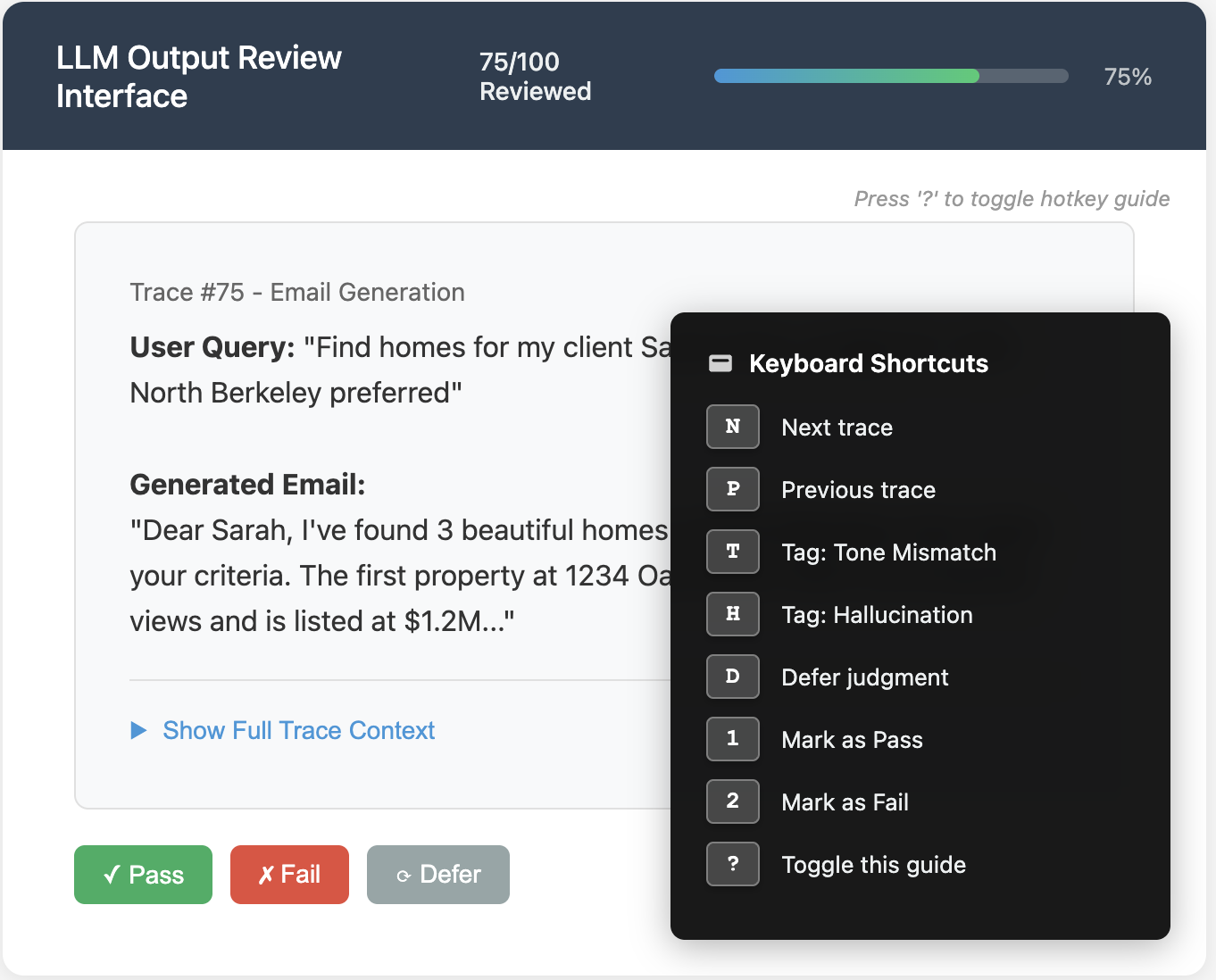

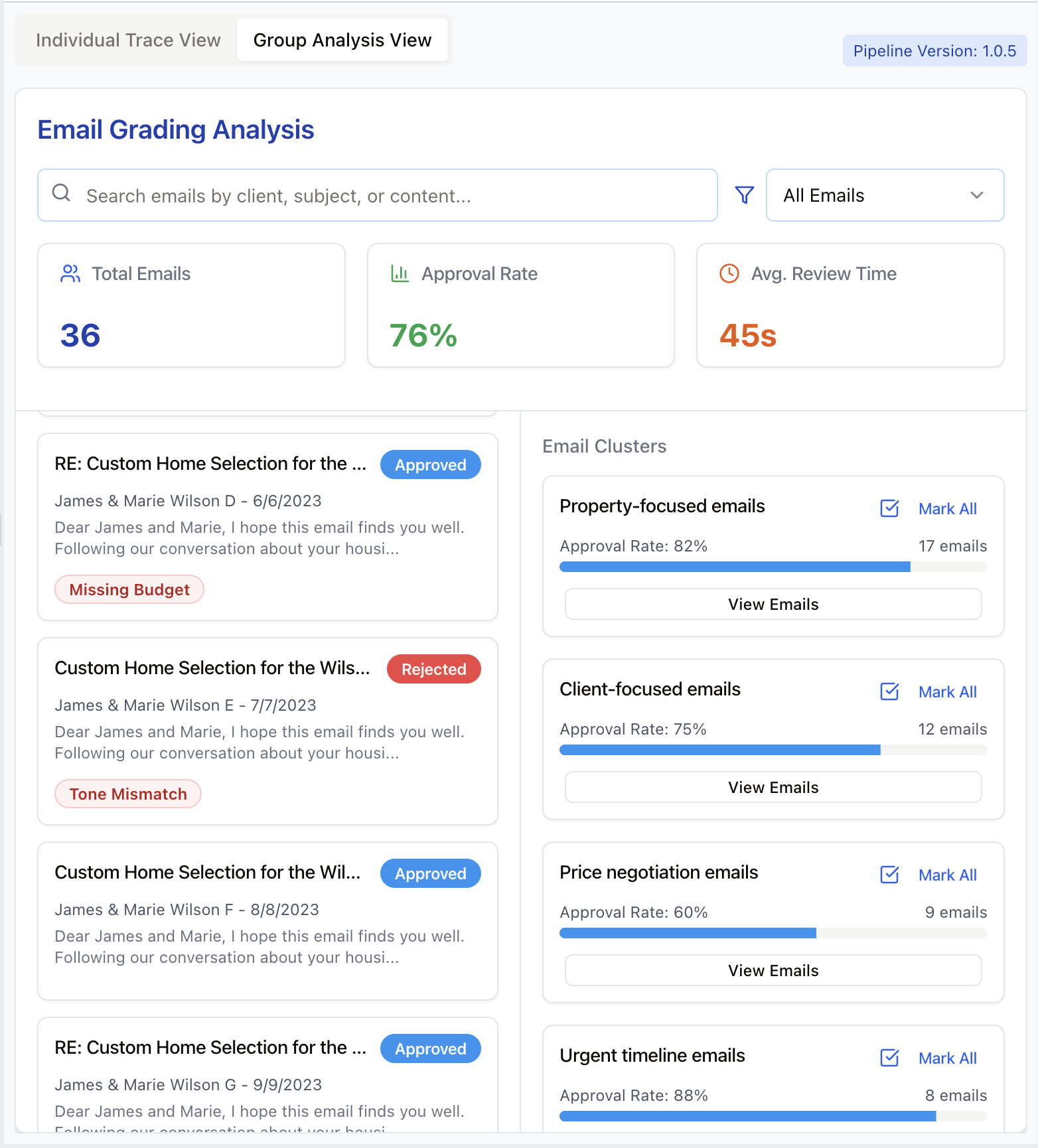

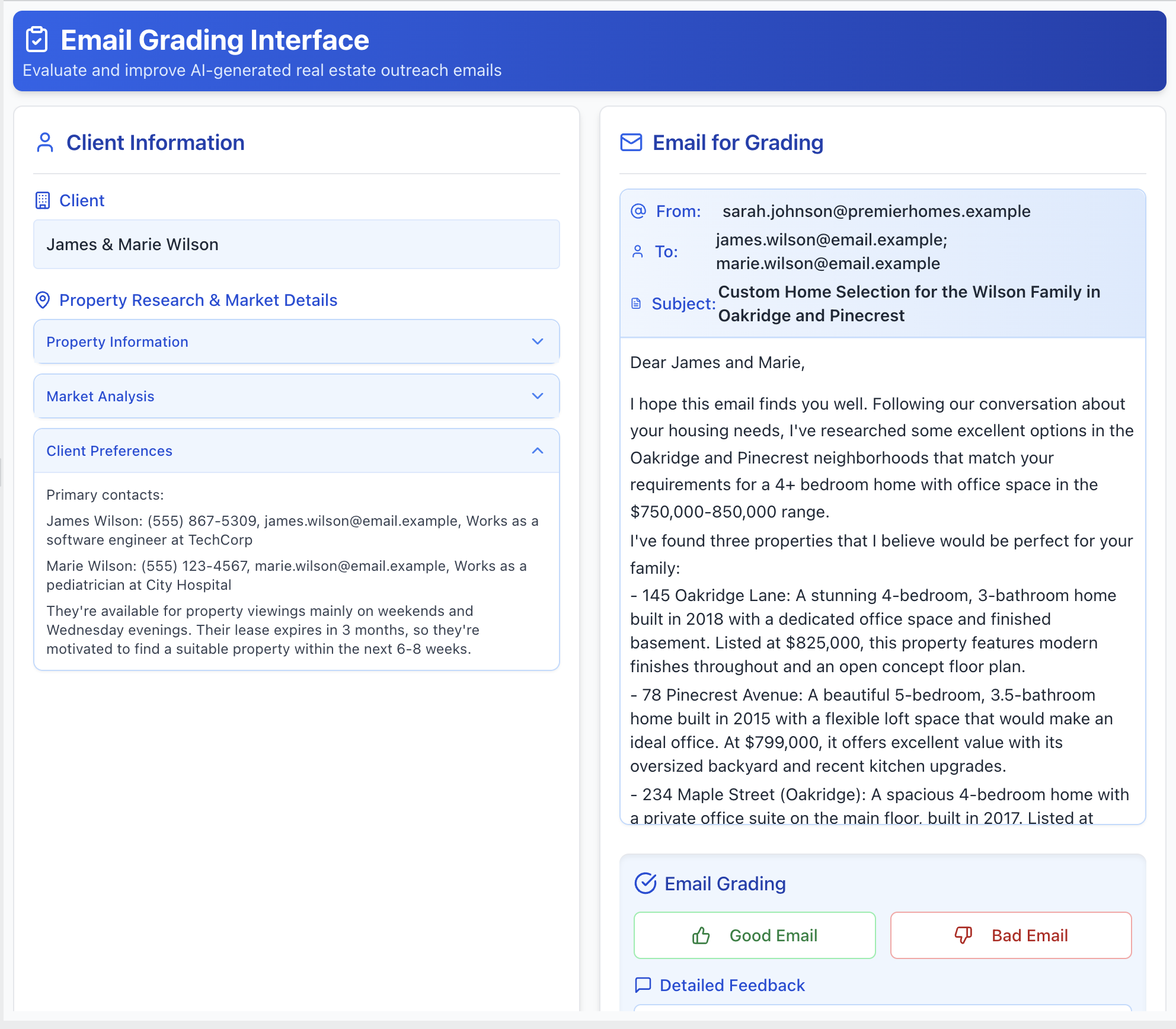

Great interfaces make human review fast, clear, and motivating. We recommend building your own annotation tool customized to your domain. The following features are possible enhancements we’ve seen work well, but you don’t need all of them. The screenshots shown are illustrative examples to clarify concepts. In practice, I rarely implement all these features in a single app. It’s ultimately a judgment call based on your specific needs and constraints.

1. Render Traces Intelligently, Not Generically:

Present the trace in a way that’s intuitive for the domain. If you’re evaluating generated emails, render them to look like emails. If the output is code, use syntax highlighting. Allow the reviewer to see the full trace (user input, tool calls, and LLM reasoning), but keep less important details in collapsed sections that can be expanded. Here is an example of a custom annotation tool for reviewing real estate assistant emails:

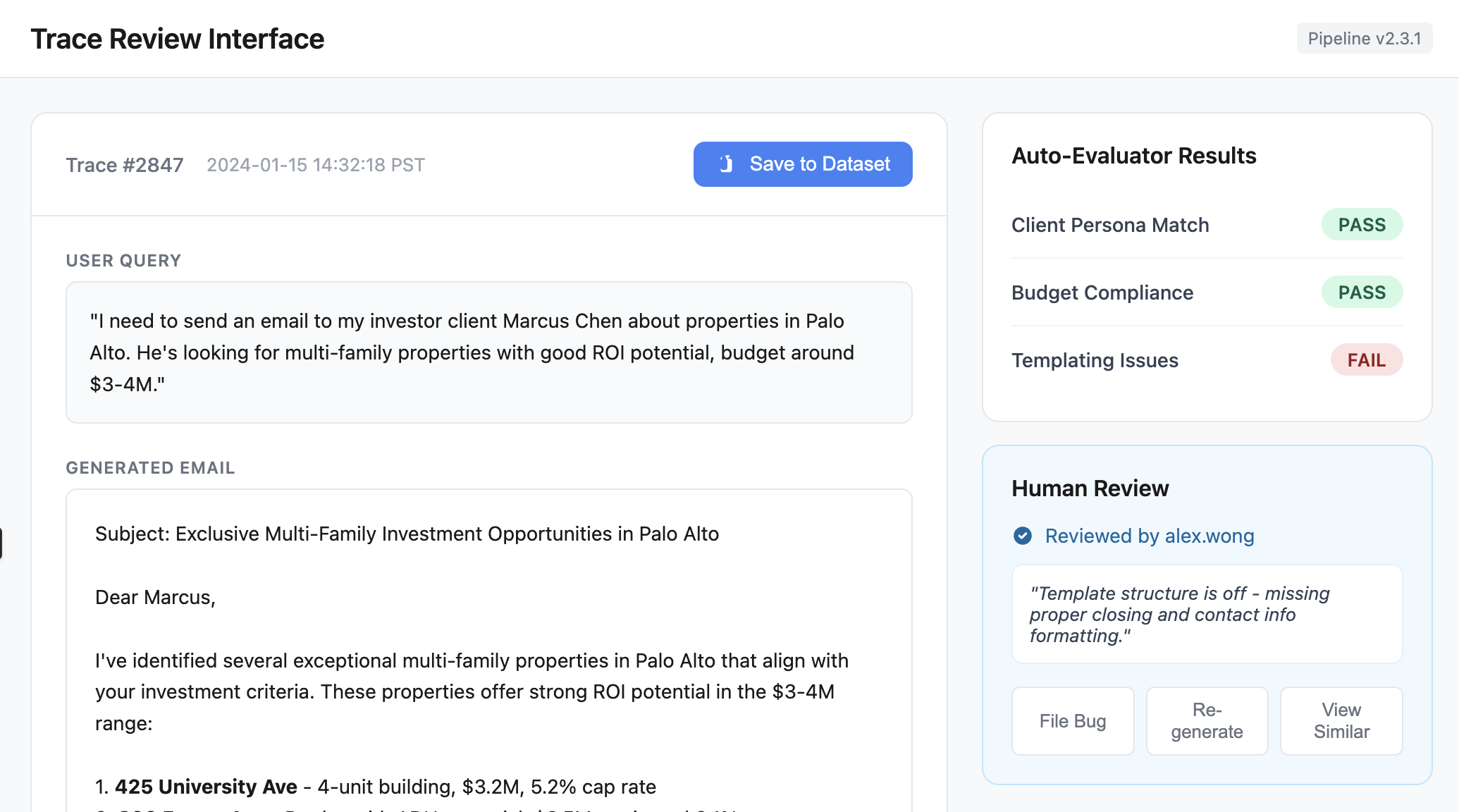

4. Prioritize labeling traces you think might be problematic:

Surface traces flagged by guardrails, CI failures, or automated evaluators for review. Provide buttons to take actions like adding to datasets, filing bugs, or re-running pipeline tests. Display relevant context (pipeline version, eval scores, reviewer info) directly in the interface to minimize context switching. Below is an illustration of these ideas:

General Principle: Keep it minimal

Keep your annotation interface minimal. Only incorporate these ideas if they provide a benefit that outweighs the additional complexity and maintenance overhead.

Q: What gaps in eval tooling should I be prepared to fill myself?

Most eval tools handle the basics well: logging complete traces, tracking metrics, prompt playgrounds, and annotation queues. These are table stakes. Here are four areas where you’ll likely need to supplement existing tools.

Watch for vendors addressing these gaps: it’s a strong signal they understand practitioner needs.

1. Error Analysis and Pattern Discovery

After reviewing traces where your AI fails, can your tooling automatically cluster similar issues? For instance, if multiple traces show the assistant using casual language for luxury clients, you need something that recognizes this broader “persona-tone mismatch” pattern. We recommend building capabilities that use AI to suggest groupings, rewrite your observations into clearer failure taxonomies, help find similar cases through semantic search, etc.

2. AI-Powered Assistance Throughout the Workflow

The most effective workflows use AI to accelerate every stage of evaluation. During error analysis, you want an LLM helping categorize your open-ended observations into coherent failure modes. For example, you might annotate several traces with notes like “wrong tone for investor,” “too casual for luxury buyer,” etc. Your tooling should recognize these as the same underlying pattern and suggest a unified “persona-tone mismatch” category.

You’ll also want AI assistance in proposing fixes. After identifying 20 cases where your assistant omits pet policies from property summaries, can your workflow analyze these failures and suggest specific prompt modifications? Can it draft refinements to your SQL generation instructions when it notices patterns of missing WHERE clauses?

Additionally, good workflows help you conduct data analysis of your annotations and traces. I like using notebooks with AI in-the-loop like Julius,Hex or SolveIt. These help me discover insights like “location ambiguity errors spike 3x when users mention neighborhood names” or “tone mismatches occur 80% more often in email generation than other modalities.”

3. Custom Evaluators Over Generic Metrics

Be prepared to build most of your evaluators from scratch. Generic metrics like “hallucination score” or “helpfulness rating” rarely capture what actually matters for your application—like proposing unavailable showing times or omitting budget constraints from emails. In our experience, successful teams spend most of their effort on application-specific metrics.

4. APIs That Support Custom Annotation Apps

Custom annotation interfaces work best for most teams. This requires observability platforms with thoughtful APIs. I often have to build my own libraries and abstractions just to make bulk data export manageable. You shouldn’t have to paginate through thousands of requests or handle timeout-prone endpoints just to get your data. Look for platforms that provide true bulk export capabilities and, crucially, APIs that let you write annotations back efficiently.

Q: What’s your favorite eval vendor?

Eval tools are in an intensely competitive space. It would be futile to compare their features. If I tried to do such an analysis, it would be invalidated in a week! Vendors I encounter the most organically in my work are: Langsmith, Arize and Braintrust.

When I help clients with vendor selection, the decision weighs heavily towards who can offer the best support, as opposed to purely features. This changes depending on size of client, use case, etc. Yes - it’s mainly the human factor that matters, and dare I say, vibes.

I have no favorite vendor. At the core, their features are very similar - and I often build custom tools on top of them to fit my needs.

Here is a video series that has a live commentary on the relative strengths and weaknesses of the three aforementioned vendors.

Q: How should I version and manage prompts?

There is an unavoidable tension between keeping prompts close to the code vs. an environment that non-technical stakeholders can access.

My preferred approach is storing prompts in Git. This treats them as software artifacts that are versioned, reviewed, and deployed atomically with the application code. While the Git command line is unfriendly for non-technical folks, the GitHub web interface and the GitHub Desktop app make it very approachable. When I was working at GitHub, I worked with many non-technical professionals, including lawyers and accountants, who used these tools effectively. Here is a blog post aimed at non-technical folks to get started.

Alternatively, most vendors in the LLM tooling space, such as observability platforms like Arize, Braintrust, and LangSmith, offer dedicated prompt management tools. These are accessible for rapid iteration but risk creating additional layers of indirection.

Why prompt management tools often fall short: AI products typically involve many moving parts: tools, RAG, agents, etc. Prompt management tools are inherently limiting because they can’t easily execute your application’s code. Even when they can, there’s often significant indirection involved, making it difficult to test prompts with your system’s capabilities.

When possible, a notebook provides a great solution for prompt experimentation If you have Python entry points into your codebase or your codebase is written in Python, Jupyter notebooks are particularly powerful for this purpose. You can experiment with prompts and iterate on your actual AI agents with their full tool and RAG capabilities. This makes it much easier to understand how your system works in practice. Additionally, you can create widgets and small user interfaces within notebooks, giving you the best of both worlds for experimentation and iteration. To see what this looks like in practice, Teresa Torres gives a fantastic, hands-on walkthrough of how she, as a PM, used notebooks for the entire eval and experimentation lifecycle:

If notebooks are not feasible for your code base, an integrated prompt environment can be effective for experimentation. Either way, I prefer to version and manage prompts in Git.

👉 Want to learn more about AI Evals? Check out our AI Evals course. It’s a live cohort with hands on exercises and office hours. Here is a 25% discount code for readers. 👈

Production & Deployment

Q: How are evaluations used differently in CI/CD vs. monitoring production?

The most important difference between CI vs. production evaluation is the data used for testing.

Test datasets for CI are small (in many cases 100+ examples) and purpose-built. Examples cover core features, regression tests for past bugs, and known edge cases. Since CI tests are run frequently, the cost of each test has to be carefully considered (that’s why you carefully curate the dataset). Favor assertions or other deterministic checks over LLM-as-judge evaluators.

For evaluating production traffic, you can sample live traces and run evaluators against them asynchronously. Since you usually lack reference outputs on production data, you might rely more on on more expensive reference-free evaluators like LLM-as-judge. Additionally, track confidence intervals for production metrics. If the lower bound crosses your threshold, investigate further.

These two systems are complementary: when production monitoring reveals new failure patterns through error analysis and evals, add representative examples to your CI dataset. This mitigates regressions on new issues.

Q: What’s the difference between guardrails & evaluators?

Guardrails are inline safety checks that sit directly in the request/response path. They validate inputs or outputs before anything reaches a user, so they typically are:

- Fast and deterministic – typically a few milliseconds of latency budget.

- Simple and explainable – regexes, keyword block-lists, schema or type validators, lightweight classifiers.

- Targeted at clear-cut, high-impact failures – PII leaks, profanity, disallowed instructions, SQL injection, malformed JSON, invalid code syntax, etc.

If a guardrail triggers, the system can redact, refuse, or regenerate the response. Because these checks are user-visible when they fire, false positives are treated as production bugs; teams version guardrail rules, log every trigger, and monitor rates to keep them conservative.

On the other hand, evaluators typically run after a response is produced. Evaluators measure qualities that simple rules cannot, such as factual correctness, completeness, etc. Their verdicts feed dashboards, regression tests, and model-improvement loops, but they do not block the original answer.

Evaluators are usually run asynchronously or in batch to afford heavier computation such as a LLM-as-a-Judge. Inline use of an LLM-as-Judge is possible only when the latency budget and reliability targets allow it. Slow LLM judges might be feasible in a cascade that runs on the minority of borderline cases.

Apply guardrails for immediate protection against objective failures requiring intervention. Use evaluators for monitoring and improving subjective or nuanced criteria. Together, they create layered protection.

Word of caution: Do not use llm guardrails off the shelf blindly. Always look at the prompt.

Q: Can my evaluators also be used to automatically fix or correct outputs in production?

Yes, but only a specific subset of them. This is the distinction between an evaluator and a guardrail that we previously discussed. As a reminder:

- Evaluators typically run asynchronously after a response has been generated. They measure quality but don’t interfere with the user’s immediate experience.

- Guardrails run synchronously in the critical path of the request, before the output is shown to the user. Their job is to prevent high-impact failures in real-time.

There are two important decision criteria for deciding whether to use an evaluator as a guardrail:

Latency & Cost: Can the evaluator run fast enough and cheaply enough in the critical request path without degrading user experience?

Error Rate Trade-offs: What’s the cost-benefit balance between false positives (blocking good outputs and frustrating users) versus false negatives (letting bad outputs reach users and causing harm)? In high-stakes domains like medical advice, false negatives may be more costly than false positives. In creative applications, false positives that block legitimate creativity may be more harmful than occasional quality issues.

Most guardrails are designed to be fast (to avoid harming user experience) and have a very low false positive rate (to avoid blocking valid responses). For this reason, you would almost never use a slow or non-deterministic LLM-as-Judge as a synchronous guardrail. However, these tradeoffs might be different for your use case.

Q: How much time should I spend on model selection?

Many developers fixate on model selection as the primary way to improve their LLM applications. Start with error analysis to understand your failure modes before considering model switching. As Hamel noted in office hours, “I suggest not thinking of switching model as the main axes of how to improve your system off the bat without evidence. Does error analysis suggest that your model is the problem?”

Domain-Specific Applications

Q: Is RAG dead?

Question: Should I avoid using RAG for my AI application after reading that “RAG is dead” for coding agents?

Many developers are confused about when and how to use RAG after reading articles claiming “RAG is dead.” Understanding what RAG actually means versus the narrow marketing definitions will help you make better architectural decisions for your AI applications.

The viral article claiming RAG is dead specifically argues against using naive vector database retrieval for autonomous coding agents, not RAG as a whole. This is a crucial distinction that many developers miss due to misleading marketing.

RAG simply means Retrieval-Augmented Generation - using retrieval to provide relevant context that improves your model’s output. The core principle remains essential: your LLM needs the right context to generate accurate answers. The question isn’t whether to use retrieval, but how to retrieve effectively.

For coding applications, naive vector similarity search often fails because code relationships are complex and contextual. Instead of abandoning retrieval entirely, modern coding assistants like Claude Code still uses retrieval —they just employ agentic search instead of relying solely on vector databases, similar to how human developers work.

You have multiple retrieval strategies available, ranging from simple keyword matching to embedding similarity to LLM-powered relevance filtering. The optimal approach depends on your specific use case, data characteristics, and performance requirements. Many production systems combine multiple strategies or use multi-hop retrieval guided by LLM agents.

Unfortunately, “RAG” has become a buzzword with no shared definition. Some people use it to mean any retrieval system, others restrict it to vector databases. Focus on the ultimate goal: getting your LLM the context it needs to succeed. Whether that’s through vector search, agentic exploration, or hybrid approaches is a product and engineering decision.

Rather than following categorical advice to avoid or embrace RAG, experiment with different retrieval approaches and measure what works best for your application. For more info on RAG evaluation and optimization, see this series of posts.

Q: How should I approach evaluating my RAG system?

RAG systems have two distinct components that require different evaluation approaches: retrieval and generation.

The retrieval component is a search problem. Evaluate it using traditional information retrieval (IR) metrics. Common examples include Recall@k (of all relevant documents, how many did you retrieve in the top k?), Precision@k (of the k documents retrieved, how many were relevant?), or MRR (how high up was the first relevant document?). The specific metrics you choose depend on your use case. These metrics are pure search metrics that measure whether you’re finding the right documents (more on this below).

To evaluate retrieval, create a dataset of queries paired with their relevant documents. Generate this synthetically by taking documents from your corpus, extracting key facts, then generating questions those facts would answer. This reverse process gives you query-document pairs for measuring retrieval performance without manual annotation.

For the generation component—how well the LLM uses retrieved context, whether it hallucinates, whether it answers the question—use the same evaluation procedures covered throughout this course: error analysis to identify failure modes, collecting human labels, building LLM-as-judge evaluators, and validating those judges against human annotations.

Jason Liu’s “There Are Only 6 RAG Evals” provides a framework that maps well to this separation. His Tier 1 covers traditional IR metrics for retrieval. Tiers 2 and 3 evaluate relationships between Question, Context, and Answer—like whether the context is relevant (C|Q), whether the answer is faithful to context (A|C), and whether the answer addresses the question (A|Q).

In addition to Jason’s six evals, error analysis on your specific data may reveal domain-specific failure modes that warrant their own metrics. For example, a medical RAG system might consistently fail to distinguish between drug dosages for adults versus children, or a legal RAG might confuse jurisdictional boundaries. These patterns emerge only through systematic review of actual failures. Once identified, you can create targeted evaluators for these specific issues beyond the general framework.

Finally, when implementing Jason’s Tier 2 and 3 metrics, don’t just use prompts off the shelf. The standard LLM-as-judge process requires several steps: error analysis, prompt iteration, creating labeled examples, and measuring your judge’s accuracy against human labels. Once you know your judge’s True Positive and True Negative rates, you can correct its estimates to determine the actual failure rate in your system. Skip this validation and your judges may not reflect your actual quality criteria.

In summary, debug retrieval first using IR metrics, then tackle generation quality using properly validated LLM judges.

Q: How do I choose the right chunk size for my document processing tasks?

Unlike RAG, where chunks are optimized for retrieval, document processing assumes the model will see every chunk. The goal is to split text so the model can reason effectively without being overwhelmed. Even if a document fits within the context window, it might be better to break it up. Long inputs can degrade performance due to attention bottlenecks, especially in the middle of the context. Two task types require different strategies:

1. Fixed-Output Tasks → Large Chunks

These are tasks where the output length doesn’t grow with input: extracting a number, answering a specific question, classifying a section. For example:

- “What’s the penalty clause in this contract?”

- “What was the CEO’s salary in 2023?”

Use the largest chunk (with caveats) that likely contains the answer. This reduces the number of queries and avoids context fragmentation. However, avoid adding irrelevant text. Models are sensitive to distraction, especially with large inputs. The middle parts of a long input might be under-attended. Furthermore, if cost and latency are a bottleneck, you should consider preprocessing or filtering the document (via keyword search or a lightweight retriever) to isolate relevant sections before feeding a huge chunk.

2. Expansive-Output Tasks → Smaller Chunks

These include summarization, exhaustive extraction, or any task where output grows with input. For example:

- “Summarize each section”

- “List all customer complaints”

In these cases, smaller chunks help preserve reasoning quality and output completeness. The standard approach is to process each chunk independently, then aggregate results (e.g., map-reduce). When sizing your chunks, try to respect content boundaries like paragraphs, sections, or chapters. Chunking also helps mitigate output limits. By breaking the task into pieces, each piece’s output can stay within limits.

General Guidance

It’s important to recognize why chunk size affects results. A larger chunk means the model has to reason over more information in one go – essentially, a heavier cognitive load. LLMs have limited capacity to retain and correlate details across a long text. If too much is packed in, the model might prioritize certain parts (commonly the beginning or end) and overlook or “forget” details in the middle. This can lead to overly coarse summaries or missed facts. In contrast, a smaller chunk bounds the problem: the model can pay full attention to that section. You are trading off global context for local focus.

No rule of thumb can perfectly determine the best chunk size for your use case – you should validate with experiments. The optimal chunk size can vary by domain and model. I treat chunk size as a hyperparameter to tune.

Q: How do I debug multi-turn conversation traces?

Start simple. Check if the whole conversation met the user’s goal with a pass/fail judgment. Look at the entire trace and focus on the first upstream failure. Read the user-visible parts first to understand if something went wrong. Only then dig into the technical details like tool calls and intermediate steps.

Multi-agent trace logging

For multi-agent flows, assign a session or trace ID to each user request and log every message with its source (which agent or tool), trace ID, and position in the sequence. This lets you reconstruct the full path from initial query to final result across all agents.

Annotation strategy

Annotate only the first failure in the trace initially—don’t worry about downstream failures since these often cascade from the first issue. Fixing upstream failures often resolves dependent downstream failures automatically. As you gain experience, you can annotate independent failure modes within the same trace to speed up overall error analysis.

Simplify when possible

When you find a failure, reproduce it with the simplest possible test case. Here’s an example: suppose a shopping bot gives the wrong return policy on turn 4 of a conversation. Before diving into the full multi-turn complexity, simplify it to a single turn: “What is the return window for product X1000?” If it still fails, you’ve proven the error isn’t about conversation context - it’s likely a basic retrieval or knowledge issue you can debug more easily.

Test case generation

You have two main approaches. First, simulate users with another LLM to create realistic multi-turn conversations. Second, use “N-1 testing” where you provide the first N-1 turns of a real conversation and test what happens next. The N-1 approach often works better since it uses actual conversation prefixes rather than fully synthetic interactions, but is less flexible.

The key is balancing thoroughness with efficiency. Not every multi-turn failure requires multi-turn analysis.

Q: How do I evaluate sessions with human handoffs?

Capture the complete user journey in your traces, including human handoffs. The trace continues until the user’s need is resolved or the session ends, not when AI hands off to a human. Log the handoff decision, why it occurred, context transferred, wait time, human actions, final resolution, and whether the human had sufficient context. Many failures occur at handoff boundaries where AI hands off too early, too late, or without proper context.

Evaluate handoffs as potential failure modes during error analysis. Ask: Was the handoff necessary? Did the AI provide adequate context? Track both handoff quality and handoff rate. Sometimes the best improvement reduces handoffs entirely rather than improving handoff execution.

Q: How do I evaluate complex multi-step workflows?

Log the entire workflow from initial trigger to final business outcome. Include LLM calls, tool usage, human approvals, and database writes in your traces. You will need this visibility to properly diagnose failures.

Use both outcome and process metrics. Outcome metrics verify the final result meets requirements: Was the business case complete? Accurate? Properly formatted? Process metrics evaluate efficiency: step count, time taken, resource usage. Process failures are often easier to debug since they’re more deterministic, so tackle them first.

Segment your error analysis by workflow stages. Early stage failures (understanding user input) differ from middle stage failures (data processing) and late stage failures (formatting output). Early stage improvements have more impact since errors cascade in LLM chains.

Use transition failure matrices to analyze where workflows break. Create a matrix showing the last successful state versus where the first failure occurred. This reveals failure hotspots and guides where to invest debugging effort.

Q: How do I evaluate agentic workflows?

We recommend evaluating agentic workflows in two phases:

1. End-to-end task success. Treat the agent as a black box and ask “did we meet the user’s goal?”. Define a precise success rule per task (exact answer, correct side-effect, etc.) and measure with human or aligned LLM judges. Take note of the first upstream failure when conducting error analysis.

Once error analysis reveals which workflows fail most often, move to step-level diagnostics to understand why they’re failing.

2. Step-level diagnostics. Assuming that you have sufficiently instrumented your system with details of tool calls and responses, you can score individual components such as: - Tool choice: was the selected tool appropriate? - Parameter extraction: were inputs complete and well-formed? - Error handling: did the agent recover from empty results or API failures? - Context retention: did it preserve earlier constraints? - Efficiency: how many steps, seconds, and tokens were spent? - Goal checkpoints: for long workflows verify key milestones.

Example: “Find Berkeley homes under $1M and schedule viewings” breaks into: parameters extracted correctly, relevant listings retrieved, availability checked, and calendar invites sent. Each checkpoint can pass or fail independently, making debugging tractable.

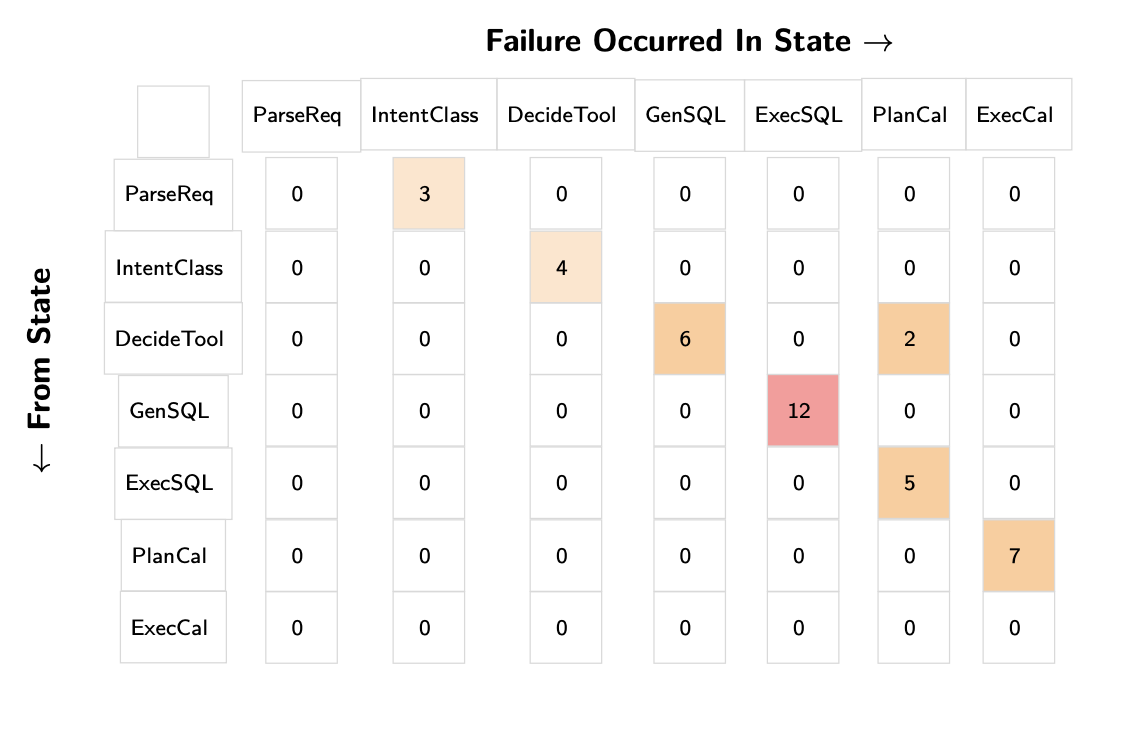

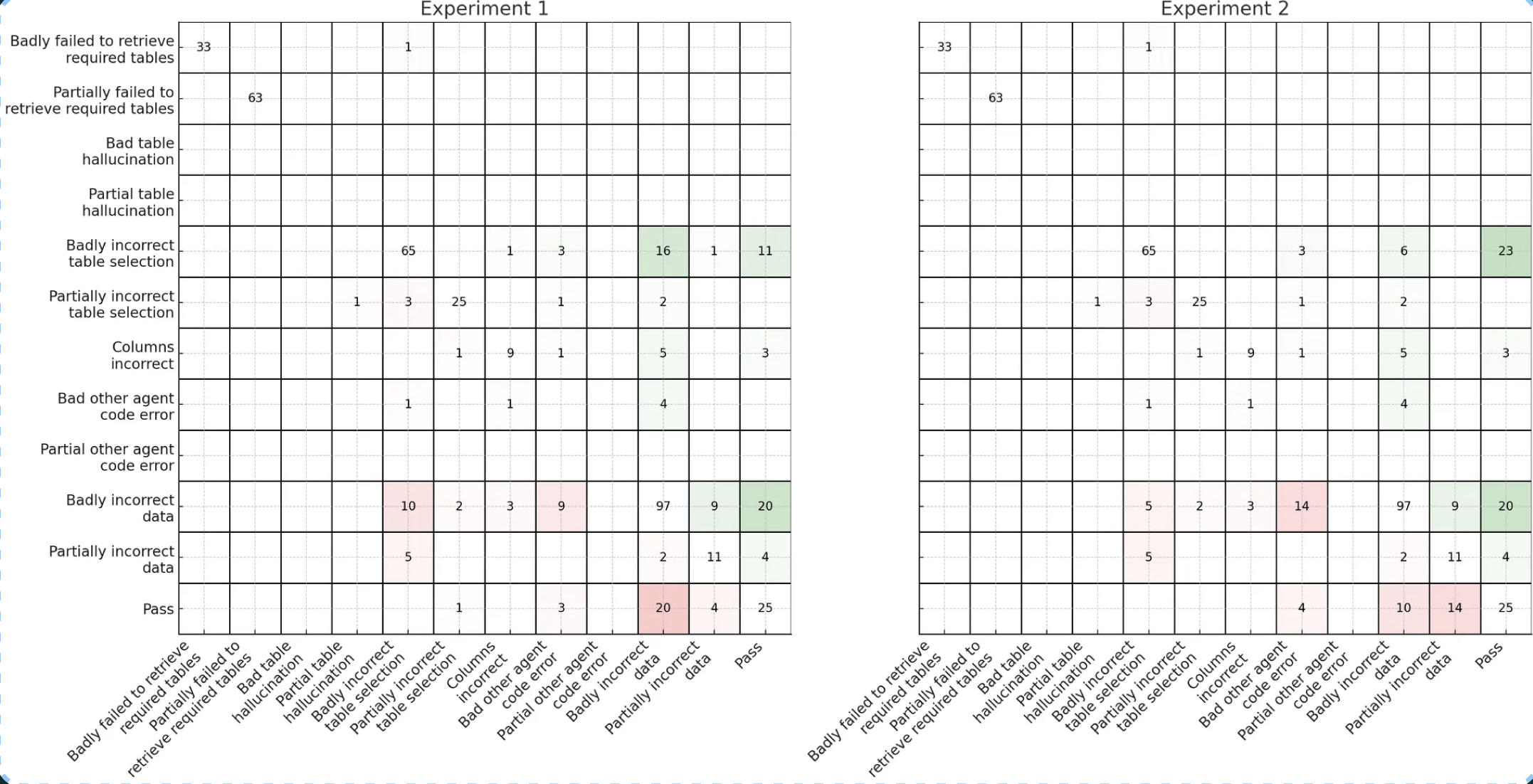

Use transition failure matrices to understand error patterns. Create a matrix where rows represent the last successful state and columns represent where the first failure occurred. This is a great way to understand where the most failures occur.

Transition matrices transform overwhelming agent complexity into actionable insights. Instead of drowning in individual trace reviews, you can immediately see that GenSQL → ExecSQL transitions cause 12 failures while DecideTool → PlanCal causes only 2. This data-driven approach guides where to invest debugging effort. Here is another example from Bryan Bischof, that is also a text-to-SQL agent:

In this example, Bryan shows variation in transition matrices across experiments. How you organize your transition matrix depends on the specifics of your application. For example, Bryan’s text-to-SQL agent has an inherent sequential workflow which he exploits for further analytical insight. You can watch his full talk for more details.

Creating Test Cases for Agent Failures

Creating test cases for agent failures follows the same principles as our previous FAQ on debugging multi-turn conversation traces (i.e. try to reproduce the error in the simplest way possible, only use multi-turn tests when the failure actually requires conversation context, etc.).

👉 Want to learn more about AI Evals? Check out our AI Evals course. It’s a live cohort with hands on exercises and office hours. Here is a 25% discount code for readers. 👈

Footnotes

Eleanor Berger, our wonderful TA.↩︎

Paul Graham, “Writes and Write-Nots”↩︎

Shreya Shankar, et al., “Who Validates the Validators? Aligning LLM-Assisted Evaluation of LLM Outputs with Human Preferences”↩︎